Mike Gesario

Spring 2009

Unit Plan

http://mikegmsu.blogspot.com/

I. The Civil War

In this unit, students will examine events, people, and issues associated with the American Civil War. The unit is designed for 10th-grade students in American history classes, but can be modified for students of other ages and abilities.

Using primary and secondary sources, photographs, films, audio recordings, and a mock trial exercise, students will use their higher-order thinking skills to gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter. Students will look at the complex series of events leading up to the war. They will experience the era through the eyes of various men and women. Students will be encouraged to make connections between the time period being studied and their world today. Students will also learn about the nature of history. They will have to investigate primary source material, as well as secondary sources, and evaluate the validity and credence of those sources.

II. New Jersey Core Curriculum Standards

Numerous standards will be realized during this unit. Among them are the following:

6.1;A1-3

Students will use historical thinking, problem solving, and research skills to maximize their understanding of the Civil War. They will analyze the historical events through primary and secondary documents, photographs, maps, and film. While using primary sources, they will investigate multiple perspectives and analyze and reconcile this information in order to evaluate the sources’ credibility.

6.4;G1

Students will demonstrate knowledge of the Civil War in order to understand life and events of the past. They will analyze key issues, events, and personalities of the period. The effects and issues surrounding John Brown’s raid, the experience and contributions of African-Americans and women during the war, and the lasting effects of the issues and events will be highlighted.

III. Historical Significance

The Civil War has been called the “most written about war in history.” It still defines the nation. There are numerous reasons students still need to be familiar with the events, people, and issues of the war.

The numerous “causes” of the war provide students with an opportunity to weigh the credibility and validity of different sources and arguments. They provide an opportunity to appreciate different points of view, while also showing the difficulty researchers and writers face while “doing history.” The contemporary reaction to John Brown’s raid and the way Brown has been taught up through recent years are examples.

The personal narratives of those who lived through the Civil War also provide an exceptional opportunity to relive history through the points of view of people from different social, racial, and geographic backgrounds. Students will see heroic episodes, but they will also see the uncertainty, violence, and sadness of the Civil War. Students will be able to see how these different stories come together to form a more accurate and complete picture of the nation’s history.

The Civil War has been romanticized in books and images ever since the opening shot was fired. Yet, the war, particularly Sherman’s March to the Sea, provides a different point of view. It provides an opportunity to discuss the concept of “total war.” Students can see the reasons for Grant’s and Sherman’s actions, while also witnessing the devastation of the operation. This example is still relevant in today’s world.

The lasting effects of the war still have a profound impact upon the face of the country – and on the way Americans think about their country. By discussing some of the lasting impacts – from the fate of the former slaves, to the nature of warfare, to the issue of war crimes, to the idea of the South’s Lost Cause – students will get a truer sense of how much or how little progress has been made since the 1860s. The Civil War provides a way to discuss some of these more complex issues.

For more, visit “Why the Civil War Still Matters” at http://hnn.us/articles/23230.html.

IV. Unit Plan

Day 1: The Civil War, Introduction and Causes

Day 2: John Brown’s Raid (Primary Source Lesson)

By reading and listening to John Brown’s final speech to the court and reading letters and editorials written either immediately before or after his execution, students will better understand the events that triggered the Civil War. By examining these sources students will also see the difficulties historians encounter while trying to write about the past.

Essential Questions:

1. How does John Brown’s story reflect the causes of the Civil War?

2. How did Americans feel about John Brown? How should history remember him now?

Day 3: The People – Life of a Soldier

Day 4: The People – The African-American Experience (Film Lesson)

The movie Glory will be used to examine the role African-American soldiers played in the Civil War. Students will examine the contributions these soldiers made, while also recognizing the difficulties they faced. Students will also have to investigate the validity of the sources being used in the lesson.

Essential Questions:

1. What was life in the army like for an African-American soldier during the Civil War? How was this experience similar to or different than the experience of a white soldier?

2. How can we use primary and secondary sources to evaluate the information presented in the movie “Glory?”

Day 5: The People – Women & The Civil War (Jigsaw Lesson)

Students will examine the lives and roles of different women during the Civil War. Each group will be assigned one woman. They will discuss the significance of these women within their groups of three or four students. The students will then share what they’ve learned about their woman with the rest of the class. Possible subjects include Bridget Divers, Mary Boykin Chesnut, Mary Ann Ball “Mother” Bickerdyke, Cornelia Hancock, Nancy Hart, Jennie Hodgers, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Susie Baker King Taylor, and Loreta Janeta Velazquez. These women represent different social, economic, geographic, and racial backgrounds.

Essential Questions:

1. How did the Civil War affect women living in different areas of the United States?

2. What contributions did women make during this time period? What concerns did they have?

Day 6: The People – Abraham Lincoln and Habeas Corpus

Day 7: The People – Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation

Day 8: The War (Geography Lesson)

Students will use photographs and illustrations, primary and secondary sources, and the Ken Burns’ Civil War documentary, to examine the reasons, motivations, and effects of Sherman’s March to the Sea and the North’s greater willingness to take the war to the heart of the Confederacy in 1864. Students will need to understand the economic, demographic, and geographic differences between the North and the South. To tie the past to the present, students will conclude the lesson by discussing if, and when, “total war” is acceptable.

Essential Questions:

1. Was Sherman’s March to the Sea justified?

2. What were the geographic, economic, and demographic similarities/differences between the North and South during the Civil War?

3. When is “total war” or “hard war” acceptable?

Day 9: New Jersey in the Civil War

Day 10: Lee’s Surrender

Day 11: Andersonville Prison (Mock Trial Lesson)

Students will reenact the trial of Henry Wirz through a mock trial. The students will analyze the testimony of each witness to determine the validity of the testimony. Students will evaluate the sources and formulate a verdict based on their judgment. The students will be asked to synthesize all of the testimony and prioritize the witnesses in order of importance. The students will relate the trial to the context of the time period. An emphasis will be placed on how the issues brought up in the trial are still relevant today.

Essential Questions:

1. What is the credibility of the evidence and sources presented in the trial? What criteria do we use to assess the value of a particular source?

2. Why was Henry Wirz the only Confederate officer put on trial after the Civil War?

3. How does society today view or define war crimes and torture? What is acceptable?

Day 12: Lasting Effects & Closing

Wednesday, May 6, 2009

Saturday, May 2, 2009

Mock Trial Exercise: Andersonville Civil War Prison

Mike Dribnack

Mike Gesario

Alex Meyer

Jonny Smith

Bryant Wanamaker

Spring 2009

Mock Trial Exercise: Andersonville Civil War Prison

I. Essential Questions

1. What is the credibility of the evidence and sources presented in the trial? What criteria do we use to assess the value of a particular source?

2. Why was Henry Wirz the only Confederate officer put on trial after the Civil War?

3. How does society today view or define war crimes and torture? What is acceptable?

II. Introduction

“There are deeds, crimes that may be forgiven but this is not among them. It steeps its perpetrators in blackest, escapeless, endless damnation” – Walt Whitman.

Andersonville prison in Georgia was the deadliest prisoner of war camp of the Civil War. The camp was in existence for 14 months. During that time, more than 45,000 Union soldiers were confined at the prison. Of these, almost 13,000 died from disease, poor sanitation, malnutrition, overcrowding, and exposure to the elements. In all, more than 40 percent of all Union prisoners of war who died during the Civil War perished at Andersonville. The largest number of prisoners held at the 26.5-acre prison at any one time was more than 32,000, during August of 1864 (http://www.nps.gov/ande/index.htm).

Both the Union and Confederacy held prisoners of war under horrible conditions. At Andersonville, the circumstances were particularly inhumane. The camp was designed to hold about 10,000 men. A stockade held thousands of men inside a barren and polluted patch of ground. Barracks were never built. Men slept in makeshift housing called “shebangs” made out of scrap wood and blankets. A small stream flowed through the compound and provided water for the Union soldiers. It also became a cesspool of disease and human waste. Erosion caused the stream to turn into a huge swamp (http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history.do?action=Article&id=2383).

Henry Wirz was the officer in charge of Andersonville. He was ordered to take responsibility for the prison in April of 1864. He assumed his duties that month and remained there until April of 1865, when he was included in General Johnston’s surrender to General Sherman.

Wirz (1822-1865) was born in Switzerland. He graduated from the University of Zurich and later obtained his doctorate degree from the medical colleges of Paris and Berlin. He immigrated to the United States in 1849 and established a practice in Kentucky. When the Civil War opened, Wirz enlisted with a regiment from Louisiana. He was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines. Though he was promoted to captain, the wound made him unfit for battle. He was sent to work with General John H. Winder, Provost Marshall in charge of Confederate prisoner of war camps. He later served at prisons in Richmond and Tuscaloosa before being sent to Andersonville (http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/Wirz/BIO1.HTM).

At the war’s end, Wirz was arrested and charged with conspiracy to injure the health and lives of Union soldiers and murder. His trial began on August 23, 1865 and lasted for about two months. During the trial, 160 witnesses were called to testify (the defense only had about 30 of those witnesses). Wirz was found guilty on Oct. 24 and was sentenced to die (http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history.do?action=Article&id=2383).

On Nov. 10, 1865, Wirz was led to the gallows in the Old Capital Prison yard. About 250 spectators who had government issued tickets watched the event. Some chanted “Remember Andersonville” as Wirz walked up to the gallows. A hood was placed over his head and rope was tied around his neck. His last words were reportedly that he was being hung for following orders. At 10:32 a.m., the trap door sprung open. Wirz’s neck was not broken by the fall. Instead, he died slowly of strangulation http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/Wirz/executin.htm).

Wirz was the only person executed by the federal government for crimes committed during the Civil War (http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history.do?action=Article&id=2383).

Though the events surrounding Andersonville and the Wirz trial took place in the 1860s, the trial still remains a source of controversy and still remains relevant in historical studies today. According to The Andersonville Prison Civil War Crimes Trial, A Headline Court Case, the trial was an important episode in the development of the laws of warfare (“following orders” is not a valid excuse for committing war crimes). It also remains a part of the larger history of the Civil War and the various interpretations and legacies of that chapter in American History. It remains to this day a symbol of the horrors of wartime cruelty.

This mock trial exercise is designed to foster students’ critical thinking abilities, as well as their abilities to weigh conflicting evidence and opinions. As indicated by the essential questions, students will have three primary tasks. First, they will need to examine the sources with a critical mindset, as they would with any historical document. Only then will they be able to determine the motives of the participants and whether the outcome of the trial was just or unjust. Secondly, students will need to place the trial into the larger context of the Civil War. They will need to examine the call for revenge in the North and will have to wrestle with the South’s perception of what happened at Andersonville, as well as what happened to Wirz. Thirdly, this trial can be used as a starting point for a discussion on similar current issues. The treatment of prisoners of war today and the use of torture during interrogations are possible related topics.

III. THE TRIAL OF HENRY WIRZ, A ROLE-PLAYING EXERCISE

(trial transcripts adapted from http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/Wirz/xrptmn.htm; Father Whelan’s testimony, Wirz’s final statement, and other selected information has been taken from The Andersonville Prison Civil War Crimes Trial, A Headline Court Case by Susan Banfield).

Characters:

Prosecuting Lawyer

Defense Lawyer

Judge

Dr. John C. Bates (witness)

A.G. Blair (witness)

George W. Gray (witness)

Edward S. Kellogg (witness)

Colonel D.T. Chandler (witness)

Lieutenant Colonel F.G. Ruffin (witness)

Augustus Moesner (witness)

Father Peter Whelan (witness)

Henry Wirz

Judge: Gentlemen, we have gathered to hear the case against Captain Henry Wirz. He faces two principal charges. First, it is charged that he maliciously, willfully, and traitorously conspired to injure the health and destroy the lives of soldiers in the military service of the United States who were being held prisoners of war…in violation of the laws and customs of war. Second, he is charged with murder, in violation of the laws and customs of war. Mr. Prosecutor, please call your first witness.

Prosecution: We first call Dr. John C. Bates…Sir, could you tell us your first impressions of Andersonville prison?

Dr. John C. Bates: I have been residing for the past four or five years in Georgia. I am a practitioner of medicine, and have been engaged in that profession since 1850. I have been on duty at the Andersonville prison as acting assistant surgeon. I was assigned there on the 19th of September, 1864 and reported for duty on the 22nd. I left there on the 29th of March 1865.

Upon going to the hospital, I went immediately to the ward to which I was assigned, and, although I am not an over-sensitive man, I must confess I was rather shocked at the appearance of things. The men were lying partially nude and dying, and lousy, a portion of them in the sand and others upon boards that had been stuck up on little props, pretty well crowded together, a majority of them in small tents that were not very serviceable at best. I went around and examined all that were placed in my charge. I became familiar with scenes of misery and they did not affect me so much.

Prosecution: Could you tell us what the men ate and what they wore?

Dr. Bates: The diet was monotonous, consisting of corn meal, peas of not very good quality, sometimes sweet potatoes, sometimes tolerably good beef, at other times not so; sometimes good bacon, at other times raw bacon, which was not good. It is my opinion that men starved to death in consequence of the paucity of the rations, especially in the fall of 1864, the quality not being very good and the quantity deficient. The meat ration was cooked at a different part of the hospital. When I would go up there, especially when I was a medical officer of the day, the men would gather around me and ask me for a bone. I would grant their requests so far as I saw bones. I would give them whatever I could find at my disposition without robbing others. I well knew when I appropriated an extra ration to one man, someone else would fall minus upon that ration. They did not presume to ask me for meat at all. It seemed to me I did express my professional opinion that men died because they could not eat the rations they got. As for clothing, we had none to give them, but the clothing of the dead was generally appropriated to the living. We thus helped the living as well as we could.

Prosecution: In your expert opinion, was there a lice problem at Andersonville?

Dr. Bates: Of vermin or lice there was a very prolific crop. I would generally find some upon myself upon returning to my quarters. It was impossible for a surgeon to enter the hospital without having some upon him when he came out.

Prosecution: What were the conditions at the hospital like?

Dr. Bates: At the hospital, I found the men destitute of clothing and bedding. There was a partial supply of fuel, but not enough to keep the men warm and prolong their existence. As a general thing, the patients were destitute. They were filthy and partly naked. There seemed to be a disposition only to get something to eat. The clamor all the while was for something to eat. They asked me for orders for this and that – peas or rice, or salt, or beef tea, or a potato, or a biscuit, or a piece of corn bread, or siftings, or meal.

Prosecution: Surely there was enough medicine and medical supplies.

Dr. Bates: Medicines were scarce. We couldn’t get what we wished. We drew upon the indigenous remedies, but they didn’t seem to work. We gathered up large quantities of them, but very few served for medicines as we wished. We were obliged to do the best we could.

Prosecution: Tell us about the teenage boy you met at the prison.

Dr. Bates: He was 15 or 16. He would often ask me to bring him a potato, a piece of bread, a biscuit, or something of that kind, which I did. I would put them in my pocket and give them to him. I would sometimes give him a raw potato, and as he had the scurvy, and also gangrene, I would advise him not to cook the potato at all, but to eat it raw, as an anti-scorbutic. I supplied him in that way for some time, but I could not give him a sufficiency. He became bed-ridden upon the hips and back, lying upon the ground. We afterwards got him some straw. Those bed-ridden sores had become gangrenous. He became more and more emaciated, until he died. The lice, the want of bed and bedding and of fuel and food, were the cause of his death. I can speak of other cases among the patients. Two or three others in my ward were in the same condition. There were others who came to their death from the bad conditions and the lack of necessary supplies. That is my professional opinion. We had cases of frostbitten feet. There was gangrene. For a while amputations were practiced in the hospital almost daily. Few successful amputations were made. I recollect two or three that were successful. In visiting the wards in the morning, I would find persons lying dead. Sometimes I would find them lying among the living. I recollect on one occasion telling my steward to go and wake up a certain one, and when I went myself to wake him up he was taking his everlasting sleep. This was in the hospital. I was not so well acquainted with how it was in the stockade. I judge, though, from what I saw, that numbers suffered in the same way there.

Prosecution: Describe what kind odors arose from that prison.

Dr. Bates: Very potent and offensive indeed.

Prosecution: From your observation of the condition and surroundings of our prisoners - their food, their drink, their exposure by day and by night, and all the circumstances you have described - state your professional opinion as to what proportion of deaths occurring there were the result of the circumstances and surroundings which you have narrated.

Dr. Bates: I feel myself safe in saying that 75 percent of those who died might have been saved, had those unfortunate men been properly cared for as to food, clothing, bedding, etc.

Prosecution: Thank you, Dr. Bates. We now call A.G. Blair…Mr. Blair, can you tell us about the treatment of prisoners at Andersonville?

A.G. Blair: Yes, sir. I was in the 122d New York. I was taken prisoner on the 23d of May, 1864, at the battle of the Wilderness. I was taken to Libby Prison first, and from that to Andersonville, where I arrived about the 1st of June. Captain Wirz was in command of the prison when I arrived there. I heard a great many questions asked to Captain Wirz about rations whenever he would come into camp. His reply was generally an oath, saying that we would get all the rations we deserved, and that was damned little.

Prosecution: Did he ever say he would not give you rations if he could?

Blair: I never heard him make that exact remark, but several days during part of my imprisonment there we had no rations. I heard from good authority that he was the cause of it, he being in charge of the camp.

Defense: I object.

Prosecution: Allow me to repeat the question. Did Captain Wirz ever say he would not give you rations if he could?

Blair: No, I never heard those words from his mouth.

Prosecution: But you did hear something similar?

Defense: I object again. We’ve already been down this road.

Judge: Overruled. Please continue.

Blair: On one occasion when he was asked by several of the prisoners who had not had any rations for 24 hours, when they were to have some food, he made remark that if the rations were in his hands we would not get any. That was in the beginning of July, 1864, just before or after the 4th. I have also seen him stand at the gate when sick men were carried out. I have seen him shove those who were well and the sick who were being carried over on their backs. Sometimes he would order the guards to do it. The condition of the men taken out of camp into the hospital was hopeless.

Blair: I escaped from Andersonville in the latter part of July or the early part of August. I got about 30 miles from the stockade when I was captured and brought back to the camp. I was kept over night, and then was put in the stocks. The first day that I was taken out of the stocks I was not put in the stockade that night. I do not recollect the exact number of hours I was kept in the stocks. Maybe five or six hours.

Prosecution: Who ordered this punishment?

Blair: I don’t know. I suppose headquarters.

Prosecution: Did you ever see a prisoner at Andersonville shot?

Blair: I saw prisoners shot on or near the deadline, on several occasions. We went to get water at the creek. The crowd there was very great since it was our only true source of water. It was absolutely necessary sometimes either to get over the deadline or to thirst. I have seen men on five or six occasions either shot dead or mortally wounded for trying to get water under the deadline. I have seen one or two instances where men were shot over the deadline. Whether they went over it intentionally, or unconsciously from not knowing the rules, I cannot say. I think that the number of men shot during my imprisonment ranged from 25 to 40. I do not know that I can give any of their names. I did know them at the time, because they had tented right around me, or messed with me, but their names have slipped my mind. Two of them belonged to the 40th New York Regiment. Those two men were shot just after I got there, in the latter part of June, 1864.

Prosecution: Did you see the person who shot them?

Blair: I saw the sentry raise his gun. I yelled to the man. I and several of the rest gave the alarm, but it was too late. One was shot through the arm. The other died. He was shot in the right breast. I did not see Captain Wirz present at the time. I did not hear any orders given to the sentinels, or any words from the sentinels when they fired. But they often said that it was done by orders from the commandant of the camp, and that they were to receive so many days furlough for every Yankee devil they killed.

Prosecution: Did you ever hear any order given by Wirz in reference to firing grape and canister on the prisoners in the stockade?

Blair: He gave an order. I did not hear it, but there was an order given . . .

Defense: This is more hearsay!

Prosecution: What order did you hear him give?

Blair: Captain Wirz planted a range of flags inside the stockade, and gave the order, just inside the gate, “that if a crowd of two hundred (that was the number) should gather in any one spot beyond those flags and near the gate, he would fire grape and canister into them.” Really, I guess, it was not so much an order as it was a simple warning.

Prosecution: We now call George W. Gray to the stand . . . Mr. Gray, how long have you been in the service?

George W. Gray: I have spent more than the last two years in the military service of the United States, in the 7th Indiana Calvary, Company B. I was taken to Andersonville on the 10th of June, 1864, and remained until November.

Prosecution: You tried to escape, didn’t you?

Gray: Yes. About the last of August I made my escape from Andersonville, and was overtaken by a lot of hounds. I climbed a tree, but the hounds circled around and barked until some Johnnies found me. They demanded that I should come down. I was brought back to Andersonville prison and taken to Wirz’s quarters. I was ordered by him to be put in the stocks, where I remained for four days, with my feet placed in a block and another lever placed over my legs, with my arms thrown back, and a chain running across my arms. At the same time a young man was placed in the stocks. He died there. He was a little sick when he went in, and he died there. I’ve forgotten the man’s name.

Prosecution: Do you know anything about Wirz having shot a prisoner of war there at any time?

Gray: He shot a young fellow named William Stewart, a private belonging to the 9th Minnesota Infantry. He and I went out of the stockade with a dead body, and after laying the dead body in the dead-house, Captain Wirz rode up to us and asked us what we were doing. Stewart said we were there by proper authority. Wirz said no more, but drew a revolver and shot the man. After he was killed the guard took from the body about $20 or $30, and Wirz took the money from the guard and rode off, telling the guard to take me to prison.

Prosecution: Can you please, for the benefit of the court, tell us if you recognize the defendant as the person who shot your comrade.

Gray (pointing to Wirz): That is the man.

Wirz: This is an outrage!

Judge: Please be quiet!

Gray: I think that is the man.

Prosecution: For our last witness, we call Edward S. Kellogg . . . Mr. Kellogg when did you arrive at Andersonville?

Edward S. Kellogg: I was in the 20th New York regiment. I was captured, and taken to Andersonville in March, 1864.

Prosecution: Did you see anyone shot at Andersonville?

Kellogg: I saw the cripple they called “Chickamauga” shot. He was shot at the south gate. He went inside the dead-line and asked to be let out. They refused to let him out. Captain Wirz ordered the guard to shoot him, and he shot him. The man lost his right leg, I believe, just above the knee. I saw other men shot while I was there. I do not know their names. They were Federal prisoners. I do not know exactly how many. I saw several. It was a common occurrence.

Prosecution: We rest our case.

Judge: Will the defense please present its case?

Defense: Yes, your honor. I would, however, first like to point out some of the very serious objections I have with this trial. First, this military court has no authority to try my client, since the war has ended.

Judge: The president has the ability to create such a military commission, through the war powers granted to him by the constitution, which are his to use in time of war and great public danger. Although the war may be over, this is still a time of great danger. The South is, afterall, still under martial law.

Defense: Secondly, this trial is unconstitutional. As your honor well knows, my client was originally charged with conspiring with several other individuals, including others at Andersonville and even higher ranking Confederate officers like Robert E. Lee. Shortly before the court was scheduled to begin proceedings, those charges were thrown out and new ones – ones that omitted Lee and other higher-ranking officers – were prepared instead. Since my client had been arraigned on almost the exact same charges once before, he should have been protected from being brought to trial again. Instead, he is being tried twice for the same crime, which is a clear violation of the constitution’s double jeopardy clause.

Judge: We have been over this before. The defendant had only been arraigned the first time, not tried. Now will you please call your first witness?

Defense: Your honor, first I would like to remind the court of the two documents that have been submitted as evidence of my client’s innocence. The letter from Ambrose Spencer, a Georgia planter and lawyer, details what he saw at Andersonville well before my client ever arrived at the place. One of the men in charge of the camp at that time, told Mr. Spencer that he intended to “build a pen…that will kill more damned Yankees that can be destroyed in the front.” I remind the court that by the time my client arrived at Andersonville, the prison was already at its capacity and conditions were greatly deteriorated. The second letter was written by my client. In it, he implores his superior officer to do something about the poor quality of the bread given to the prisoners. Nothing was ever done about his request.

Judge: Very well. We have entered these two documents into the record. Please call your witness.

Defense: Your honor, I’d first like to call Colonel D.T. Chandler. As you know, Colonel Chandler inspected the prison at Andersonville and reported his findings to the Confederate government… Dr. Chandler, can you give us a brief overview of your findings at Andersonville?

Colonel D.T. Chandler: My report describes the problems with the water supply, particularly the dumping of refuse into the stream by the cookhouse and its use as a toilet, the problems arising from a lack of shelter, the lack of any systematic arrangement of the prisoners’ tents, the insufficient and poor quality of the food, and the problems arising from issuing rations uncooked without providing wood or utensils for cooking. I was especially disgusted by the conditions of the hospital and the general lack of sanitation throughout the prison.

Defense: You included suggestions with your report, didn’t you?

Chandler: Yes. I made numerous recommendations for improving the conditions at Andersonville. I suggested providing fresh vegetables, clothing, soap, medicines and bedding – and of course reducing the overcrowding by sending some of the prisoners away and not allowing any more to enter. I urged General Winder to do something about the terrible conditions.

Defense: The General Winder who was in charge of all prisoner of war camps in the Confederacy?

Chandler: Yes.

Defense: And what did he say?

Chandler: When I spoke of the great mortality existing among the prisoners, he replied to me that he thought it was better to let half of them die than to take care of the men.

Defense: Thank you, Colonel. Next, I’d like to call Lieutenant Colonel F.G. Ruffin…Lieutenant Colonel, you served in the subsistence department of the Confederate Army, didn’t you?

Lieutenant Colonel F.G. Ruffin: Yes, sir.

Defense: Was it easy supplying the army with food?

Ruffin: No, sir, of course not. From the beginning, there was more of less scarcity. We reduced rations at just about every level. The generals all complained, because they said they couldn’t keep their armies together on what we were giving them. But we couldn’t help it.

Defense: Thank you, Lieutenant Colonel. That will be all. Your honor, I’d like to now call Augustus Moesner, who can testify on whether Captain Wirz ever violated the rules of war. Mr. Moesner, in your experience as a guard at Andersonville, how did Captain Wirz feel about having young boys being held prisoner?

Augustus Moesner: I remember that there were about 40 or 50 boys inside the stockade, who had been taken prisoners, and Captain Wirz requested Dr. White to take some of them to the hospital as helps to the nurses or cooks there, because it was no use to keep those boys as prisoners of war. They would only get sick and die inside the stockade.

Defense: And what was the rule in regard to prisoners who got sick?

Moesner: Well, sir, when a man who had been ordered to wear a ball and chain complained that he was sick, a doctor was sent for, and if he found that it was so, the ball and chain would be taken off and the man would be sent to the hospital if necessary. Also, when new squads of prisoners came in, and there were men among them who claimed to be sick, a doctor was sent for. If the men were really sick, they were sent to the hospital. I also recollect also that once there was a man amongst them who told me he was a hospital steward in the army. I spoke to Captain Wirz about it, and the man was immediately sent to the hospital as a steward. He was paroled and was not sent into the stockade at all.

Defense: Did you at your headquarters or did Captain Wirz have anything to do with vaccination?

Moesner: I remember Dr. White gave an order, as the small-pox was increasing among the prisoners, that all men who came as new prisoners to Andersonville, who had not been vaccinated, should be vaccinated. But the order had been given by Dr. White and not by Captain Wirz. I remember Wirz once saying he would not care a damn whether they died of small-pox or not.

Defense: Do you know anything about Frado or “Frenchy,” who was brought in by the dogs?

Moesner: Frado was a Frenchman. He escaped seven times. I saw him brought back with a ball and chain on him once. A short time afterwards he escaped again. I don’t know how. The last time, he was brought back and sent to the stockade. Captain Wirz said he saw it was of no use of putting him in irons again. Rumor has it, they let the dogs at him. I saw only that his pants were torn up. I did not see that the dogs had hurt him. In fact, I never saw, knew, or heard of anybody dying at Captain Wirz’s headquarters who had been bitten by dogs. I never saw, knew, or head about Captain Wirz shooting, beating, or killing men in any way while I was there. I never saw, knew, or heard in any way of Captain Wirz carrying a whip while I was there. He never did.

Defense: But surely he had the power to punish the prisoners?

Moesner: Captain Wirz had the power to inflict other punishment besides putting men in the stocks. He had the power to put the ball and chain on them. I never saw a man bucked and gagged while I was at Andersonville. I don't know whether he could issue the order on that subject. I don't know how far his power went. I know of Captain Wirz ordering men to be whipped. I have heard him give the order to whip a man. That is another thing he had power to do. Captain Wirz had the power and exercised the power to direct that prisoners be caught by the hounds. He had that power. He put them in the stocks. I don't recollect any other punishments than what I have mentioned. Although Captain Wirz had the power to inflict all these other punishments, he had no power to put men in the chaingang, so far as I know, and I know about that just as I know about everything else. I never heard of Captain Wirz shooting, kicking, or beating a Federal prisoner while I was at Andersonville. I swear positively to that; I saw him pushing prisoners into the ranks, but not that they could be hurt. He was violent in these moments, cursing and swearing, as he always was with us, but he seemed harder than he was.

Defense: You swear positively that you never heard of a man being torn by the hounds?

Moesner: I saw that Frenchy had his pants torn. That is the only instance of hounds tearing the soldiers' clothes or flesh that I ever heard of.

Defense: Thank you. We now call Father Peter Whelan…Father, can you tell us of your experiences at Andersonville?

Father Peter Whelan: As a Roman Catholic priest, I spent more than three months at Andersonville ministering to those of the faith and to others in need of spiritual comfort. I was often inside the stockade from 9 a.m. to 4 or 5 p.m. from mid-June to about the beginning of October 1864.

Defense: From your intimacy with Captain Wirz while you were there, can you tell us what his general conduct, as to kindness or harshness, toward the prisoners was like?

Father Whelan: He was always calm and kind to me.

Defense: Was he to others, so far as you saw?

Father Whelan: Yes, sir. I have seen him commit no violence. He may sometimes have spoken harshly to some of the prisoners…There have been some violence charged upon him here which I never heard of being committed by him. I never heard of his killing a man, or striking a man with a pistol, or kicking a man to death. During my time in the stockade, I never heard of it. I never heard, either inside or outside, during my stay there, that he had taken the life of a man by violence.

Defense: If any such thing occurred, must you not have heard of it?

Father Whelan: It is highly probable I should have heard of it.

Defense: Your honor, the defense rests.

Judge: Very well. Will the prosecution make its closing argument?

Prosecution: Your honor, more than 100 witnesses have come forward to help the prosecution make its case. The evidence points to the truth. Mortal man has never been called to answer before a legal tribunal to a catalogue of crime like this. One shudders at the fact, and almost doubts the age we live in. I would not harrow up your minds by dwelling further upon this woeful record. The obligation you have taken constitutes you the sole judges of both law and fact. I pray you administer the one, and decide the other. To the defense’s complaints about the alleged vagueness of some of the testimony, we say, naturally the prisoners’ memories are a bit jumbled. They had in many cases lost track of what day, or even what month it was. They also witnessed so many horrible incidents on a daily basis that it should not be surprising if they were unable to fix with certainty an exact date of one in particular. And to the assertion that the defendant was only following orders we say that a superior officer cannot order a subordinate to do an illegal act, and if a subordinate obey such an order and disastrous consequences result, both the superior and the subordinate must answer for it!

Judge: Would the defendant like to make a final statement?

Henry Wirz: Yes, your honor. I am no lawyer, gentlemen, and this statement is prepared without the aid of my counsel…A poor subaltern officer should not be called upon to bear upon his overburdened shoulders the faults and misdeeds of others…It cannot be expected, neither law nor justice requires, that I should be able to defend myself against the vague allegations, the murky, foggy, indefinite, and contradictory testimony…The alleged murder of a prisoner named Chickamauga was described by at least 20 witnesses – and in as many different versions…William Stewart, another soldier I allegedly murdered, is as much a creation of the fertile imagination of the witness who testified to his murder by me as the conspiracy charged against me is a creation of the fancy of the prosecution…This court…is composed of brave, honorable, and enlightened officers, who have the ability, I am sure, to distinguish the real from the fictitious in this case, the honesty to rise above popular clamor and public misrepresentations…I cannot believe that they will consent to…consign to a felon’s doom a poor subaltern officer, who, in a different post, sought to do his duty and did it…May god so direct and enlighten you in your deliberations that your reputation for impartiality and justice may be upheld, my character vindicated, and the few days of my natural life spared to my helpless family.

Mike Gesario

Alex Meyer

Jonny Smith

Bryant Wanamaker

Spring 2009

Mock Trial Exercise: Andersonville Civil War Prison

I. Essential Questions

1. What is the credibility of the evidence and sources presented in the trial? What criteria do we use to assess the value of a particular source?

2. Why was Henry Wirz the only Confederate officer put on trial after the Civil War?

3. How does society today view or define war crimes and torture? What is acceptable?

II. Introduction

“There are deeds, crimes that may be forgiven but this is not among them. It steeps its perpetrators in blackest, escapeless, endless damnation” – Walt Whitman.

Andersonville prison in Georgia was the deadliest prisoner of war camp of the Civil War. The camp was in existence for 14 months. During that time, more than 45,000 Union soldiers were confined at the prison. Of these, almost 13,000 died from disease, poor sanitation, malnutrition, overcrowding, and exposure to the elements. In all, more than 40 percent of all Union prisoners of war who died during the Civil War perished at Andersonville. The largest number of prisoners held at the 26.5-acre prison at any one time was more than 32,000, during August of 1864 (http://www.nps.gov/ande/index.htm).

Both the Union and Confederacy held prisoners of war under horrible conditions. At Andersonville, the circumstances were particularly inhumane. The camp was designed to hold about 10,000 men. A stockade held thousands of men inside a barren and polluted patch of ground. Barracks were never built. Men slept in makeshift housing called “shebangs” made out of scrap wood and blankets. A small stream flowed through the compound and provided water for the Union soldiers. It also became a cesspool of disease and human waste. Erosion caused the stream to turn into a huge swamp (http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history.do?action=Article&id=2383).

Henry Wirz was the officer in charge of Andersonville. He was ordered to take responsibility for the prison in April of 1864. He assumed his duties that month and remained there until April of 1865, when he was included in General Johnston’s surrender to General Sherman.

Wirz (1822-1865) was born in Switzerland. He graduated from the University of Zurich and later obtained his doctorate degree from the medical colleges of Paris and Berlin. He immigrated to the United States in 1849 and established a practice in Kentucky. When the Civil War opened, Wirz enlisted with a regiment from Louisiana. He was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines. Though he was promoted to captain, the wound made him unfit for battle. He was sent to work with General John H. Winder, Provost Marshall in charge of Confederate prisoner of war camps. He later served at prisons in Richmond and Tuscaloosa before being sent to Andersonville (http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/Wirz/BIO1.HTM).

At the war’s end, Wirz was arrested and charged with conspiracy to injure the health and lives of Union soldiers and murder. His trial began on August 23, 1865 and lasted for about two months. During the trial, 160 witnesses were called to testify (the defense only had about 30 of those witnesses). Wirz was found guilty on Oct. 24 and was sentenced to die (http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history.do?action=Article&id=2383).

On Nov. 10, 1865, Wirz was led to the gallows in the Old Capital Prison yard. About 250 spectators who had government issued tickets watched the event. Some chanted “Remember Andersonville” as Wirz walked up to the gallows. A hood was placed over his head and rope was tied around his neck. His last words were reportedly that he was being hung for following orders. At 10:32 a.m., the trap door sprung open. Wirz’s neck was not broken by the fall. Instead, he died slowly of strangulation http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/Wirz/executin.htm).

Wirz was the only person executed by the federal government for crimes committed during the Civil War (http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history.do?action=Article&id=2383).

Though the events surrounding Andersonville and the Wirz trial took place in the 1860s, the trial still remains a source of controversy and still remains relevant in historical studies today. According to The Andersonville Prison Civil War Crimes Trial, A Headline Court Case, the trial was an important episode in the development of the laws of warfare (“following orders” is not a valid excuse for committing war crimes). It also remains a part of the larger history of the Civil War and the various interpretations and legacies of that chapter in American History. It remains to this day a symbol of the horrors of wartime cruelty.

This mock trial exercise is designed to foster students’ critical thinking abilities, as well as their abilities to weigh conflicting evidence and opinions. As indicated by the essential questions, students will have three primary tasks. First, they will need to examine the sources with a critical mindset, as they would with any historical document. Only then will they be able to determine the motives of the participants and whether the outcome of the trial was just or unjust. Secondly, students will need to place the trial into the larger context of the Civil War. They will need to examine the call for revenge in the North and will have to wrestle with the South’s perception of what happened at Andersonville, as well as what happened to Wirz. Thirdly, this trial can be used as a starting point for a discussion on similar current issues. The treatment of prisoners of war today and the use of torture during interrogations are possible related topics.

III. THE TRIAL OF HENRY WIRZ, A ROLE-PLAYING EXERCISE

(trial transcripts adapted from http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/Wirz/xrptmn.htm; Father Whelan’s testimony, Wirz’s final statement, and other selected information has been taken from The Andersonville Prison Civil War Crimes Trial, A Headline Court Case by Susan Banfield).

Characters:

Prosecuting Lawyer

Defense Lawyer

Judge

Dr. John C. Bates (witness)

A.G. Blair (witness)

George W. Gray (witness)

Edward S. Kellogg (witness)

Colonel D.T. Chandler (witness)

Lieutenant Colonel F.G. Ruffin (witness)

Augustus Moesner (witness)

Father Peter Whelan (witness)

Henry Wirz

Judge: Gentlemen, we have gathered to hear the case against Captain Henry Wirz. He faces two principal charges. First, it is charged that he maliciously, willfully, and traitorously conspired to injure the health and destroy the lives of soldiers in the military service of the United States who were being held prisoners of war…in violation of the laws and customs of war. Second, he is charged with murder, in violation of the laws and customs of war. Mr. Prosecutor, please call your first witness.

Prosecution: We first call Dr. John C. Bates…Sir, could you tell us your first impressions of Andersonville prison?

Dr. John C. Bates: I have been residing for the past four or five years in Georgia. I am a practitioner of medicine, and have been engaged in that profession since 1850. I have been on duty at the Andersonville prison as acting assistant surgeon. I was assigned there on the 19th of September, 1864 and reported for duty on the 22nd. I left there on the 29th of March 1865.

Upon going to the hospital, I went immediately to the ward to which I was assigned, and, although I am not an over-sensitive man, I must confess I was rather shocked at the appearance of things. The men were lying partially nude and dying, and lousy, a portion of them in the sand and others upon boards that had been stuck up on little props, pretty well crowded together, a majority of them in small tents that were not very serviceable at best. I went around and examined all that were placed in my charge. I became familiar with scenes of misery and they did not affect me so much.

Prosecution: Could you tell us what the men ate and what they wore?

Dr. Bates: The diet was monotonous, consisting of corn meal, peas of not very good quality, sometimes sweet potatoes, sometimes tolerably good beef, at other times not so; sometimes good bacon, at other times raw bacon, which was not good. It is my opinion that men starved to death in consequence of the paucity of the rations, especially in the fall of 1864, the quality not being very good and the quantity deficient. The meat ration was cooked at a different part of the hospital. When I would go up there, especially when I was a medical officer of the day, the men would gather around me and ask me for a bone. I would grant their requests so far as I saw bones. I would give them whatever I could find at my disposition without robbing others. I well knew when I appropriated an extra ration to one man, someone else would fall minus upon that ration. They did not presume to ask me for meat at all. It seemed to me I did express my professional opinion that men died because they could not eat the rations they got. As for clothing, we had none to give them, but the clothing of the dead was generally appropriated to the living. We thus helped the living as well as we could.

Prosecution: In your expert opinion, was there a lice problem at Andersonville?

Dr. Bates: Of vermin or lice there was a very prolific crop. I would generally find some upon myself upon returning to my quarters. It was impossible for a surgeon to enter the hospital without having some upon him when he came out.

Prosecution: What were the conditions at the hospital like?

Dr. Bates: At the hospital, I found the men destitute of clothing and bedding. There was a partial supply of fuel, but not enough to keep the men warm and prolong their existence. As a general thing, the patients were destitute. They were filthy and partly naked. There seemed to be a disposition only to get something to eat. The clamor all the while was for something to eat. They asked me for orders for this and that – peas or rice, or salt, or beef tea, or a potato, or a biscuit, or a piece of corn bread, or siftings, or meal.

Prosecution: Surely there was enough medicine and medical supplies.

Dr. Bates: Medicines were scarce. We couldn’t get what we wished. We drew upon the indigenous remedies, but they didn’t seem to work. We gathered up large quantities of them, but very few served for medicines as we wished. We were obliged to do the best we could.

Prosecution: Tell us about the teenage boy you met at the prison.

Dr. Bates: He was 15 or 16. He would often ask me to bring him a potato, a piece of bread, a biscuit, or something of that kind, which I did. I would put them in my pocket and give them to him. I would sometimes give him a raw potato, and as he had the scurvy, and also gangrene, I would advise him not to cook the potato at all, but to eat it raw, as an anti-scorbutic. I supplied him in that way for some time, but I could not give him a sufficiency. He became bed-ridden upon the hips and back, lying upon the ground. We afterwards got him some straw. Those bed-ridden sores had become gangrenous. He became more and more emaciated, until he died. The lice, the want of bed and bedding and of fuel and food, were the cause of his death. I can speak of other cases among the patients. Two or three others in my ward were in the same condition. There were others who came to their death from the bad conditions and the lack of necessary supplies. That is my professional opinion. We had cases of frostbitten feet. There was gangrene. For a while amputations were practiced in the hospital almost daily. Few successful amputations were made. I recollect two or three that were successful. In visiting the wards in the morning, I would find persons lying dead. Sometimes I would find them lying among the living. I recollect on one occasion telling my steward to go and wake up a certain one, and when I went myself to wake him up he was taking his everlasting sleep. This was in the hospital. I was not so well acquainted with how it was in the stockade. I judge, though, from what I saw, that numbers suffered in the same way there.

Prosecution: Describe what kind odors arose from that prison.

Dr. Bates: Very potent and offensive indeed.

Prosecution: From your observation of the condition and surroundings of our prisoners - their food, their drink, their exposure by day and by night, and all the circumstances you have described - state your professional opinion as to what proportion of deaths occurring there were the result of the circumstances and surroundings which you have narrated.

Dr. Bates: I feel myself safe in saying that 75 percent of those who died might have been saved, had those unfortunate men been properly cared for as to food, clothing, bedding, etc.

Prosecution: Thank you, Dr. Bates. We now call A.G. Blair…Mr. Blair, can you tell us about the treatment of prisoners at Andersonville?

A.G. Blair: Yes, sir. I was in the 122d New York. I was taken prisoner on the 23d of May, 1864, at the battle of the Wilderness. I was taken to Libby Prison first, and from that to Andersonville, where I arrived about the 1st of June. Captain Wirz was in command of the prison when I arrived there. I heard a great many questions asked to Captain Wirz about rations whenever he would come into camp. His reply was generally an oath, saying that we would get all the rations we deserved, and that was damned little.

Prosecution: Did he ever say he would not give you rations if he could?

Blair: I never heard him make that exact remark, but several days during part of my imprisonment there we had no rations. I heard from good authority that he was the cause of it, he being in charge of the camp.

Defense: I object.

Prosecution: Allow me to repeat the question. Did Captain Wirz ever say he would not give you rations if he could?

Blair: No, I never heard those words from his mouth.

Prosecution: But you did hear something similar?

Defense: I object again. We’ve already been down this road.

Judge: Overruled. Please continue.

Blair: On one occasion when he was asked by several of the prisoners who had not had any rations for 24 hours, when they were to have some food, he made remark that if the rations were in his hands we would not get any. That was in the beginning of July, 1864, just before or after the 4th. I have also seen him stand at the gate when sick men were carried out. I have seen him shove those who were well and the sick who were being carried over on their backs. Sometimes he would order the guards to do it. The condition of the men taken out of camp into the hospital was hopeless.

Prosecution: You escaped briefly. What happened when you were re-captured?

Blair: I escaped from Andersonville in the latter part of July or the early part of August. I got about 30 miles from the stockade when I was captured and brought back to the camp. I was kept over night, and then was put in the stocks. The first day that I was taken out of the stocks I was not put in the stockade that night. I do not recollect the exact number of hours I was kept in the stocks. Maybe five or six hours.

Prosecution: Who ordered this punishment?

Blair: I don’t know. I suppose headquarters.

Prosecution: Did you ever see a prisoner at Andersonville shot?

Blair: I saw prisoners shot on or near the deadline, on several occasions. We went to get water at the creek. The crowd there was very great since it was our only true source of water. It was absolutely necessary sometimes either to get over the deadline or to thirst. I have seen men on five or six occasions either shot dead or mortally wounded for trying to get water under the deadline. I have seen one or two instances where men were shot over the deadline. Whether they went over it intentionally, or unconsciously from not knowing the rules, I cannot say. I think that the number of men shot during my imprisonment ranged from 25 to 40. I do not know that I can give any of their names. I did know them at the time, because they had tented right around me, or messed with me, but their names have slipped my mind. Two of them belonged to the 40th New York Regiment. Those two men were shot just after I got there, in the latter part of June, 1864.

Prosecution: Did you see the person who shot them?

Blair: I saw the sentry raise his gun. I yelled to the man. I and several of the rest gave the alarm, but it was too late. One was shot through the arm. The other died. He was shot in the right breast. I did not see Captain Wirz present at the time. I did not hear any orders given to the sentinels, or any words from the sentinels when they fired. But they often said that it was done by orders from the commandant of the camp, and that they were to receive so many days furlough for every Yankee devil they killed.

Prosecution: Did you ever hear any order given by Wirz in reference to firing grape and canister on the prisoners in the stockade?

Blair: He gave an order. I did not hear it, but there was an order given . . .

Defense: This is more hearsay!

Prosecution: What order did you hear him give?

Blair: Captain Wirz planted a range of flags inside the stockade, and gave the order, just inside the gate, “that if a crowd of two hundred (that was the number) should gather in any one spot beyond those flags and near the gate, he would fire grape and canister into them.” Really, I guess, it was not so much an order as it was a simple warning.

Prosecution: We now call George W. Gray to the stand . . . Mr. Gray, how long have you been in the service?

George W. Gray: I have spent more than the last two years in the military service of the United States, in the 7th Indiana Calvary, Company B. I was taken to Andersonville on the 10th of June, 1864, and remained until November.

Prosecution: You tried to escape, didn’t you?

Gray: Yes. About the last of August I made my escape from Andersonville, and was overtaken by a lot of hounds. I climbed a tree, but the hounds circled around and barked until some Johnnies found me. They demanded that I should come down. I was brought back to Andersonville prison and taken to Wirz’s quarters. I was ordered by him to be put in the stocks, where I remained for four days, with my feet placed in a block and another lever placed over my legs, with my arms thrown back, and a chain running across my arms. At the same time a young man was placed in the stocks. He died there. He was a little sick when he went in, and he died there. I’ve forgotten the man’s name.

Prosecution: Do you know anything about Wirz having shot a prisoner of war there at any time?

Gray: He shot a young fellow named William Stewart, a private belonging to the 9th Minnesota Infantry. He and I went out of the stockade with a dead body, and after laying the dead body in the dead-house, Captain Wirz rode up to us and asked us what we were doing. Stewart said we were there by proper authority. Wirz said no more, but drew a revolver and shot the man. After he was killed the guard took from the body about $20 or $30, and Wirz took the money from the guard and rode off, telling the guard to take me to prison.

Prosecution: Can you please, for the benefit of the court, tell us if you recognize the defendant as the person who shot your comrade.

Gray (pointing to Wirz): That is the man.

Wirz: This is an outrage!

Judge: Please be quiet!

Gray: I think that is the man.

Prosecution: For our last witness, we call Edward S. Kellogg . . . Mr. Kellogg when did you arrive at Andersonville?

Edward S. Kellogg: I was in the 20th New York regiment. I was captured, and taken to Andersonville in March, 1864.

Prosecution: Did you see anyone shot at Andersonville?

Kellogg: I saw the cripple they called “Chickamauga” shot. He was shot at the south gate. He went inside the dead-line and asked to be let out. They refused to let him out. Captain Wirz ordered the guard to shoot him, and he shot him. The man lost his right leg, I believe, just above the knee. I saw other men shot while I was there. I do not know their names. They were Federal prisoners. I do not know exactly how many. I saw several. It was a common occurrence.

Prosecution: We rest our case.

Judge: Will the defense please present its case?

Defense: Yes, your honor. I would, however, first like to point out some of the very serious objections I have with this trial. First, this military court has no authority to try my client, since the war has ended.

Judge: The president has the ability to create such a military commission, through the war powers granted to him by the constitution, which are his to use in time of war and great public danger. Although the war may be over, this is still a time of great danger. The South is, afterall, still under martial law.

Defense: Secondly, this trial is unconstitutional. As your honor well knows, my client was originally charged with conspiring with several other individuals, including others at Andersonville and even higher ranking Confederate officers like Robert E. Lee. Shortly before the court was scheduled to begin proceedings, those charges were thrown out and new ones – ones that omitted Lee and other higher-ranking officers – were prepared instead. Since my client had been arraigned on almost the exact same charges once before, he should have been protected from being brought to trial again. Instead, he is being tried twice for the same crime, which is a clear violation of the constitution’s double jeopardy clause.

Judge: We have been over this before. The defendant had only been arraigned the first time, not tried. Now will you please call your first witness?

Defense: Your honor, first I would like to remind the court of the two documents that have been submitted as evidence of my client’s innocence. The letter from Ambrose Spencer, a Georgia planter and lawyer, details what he saw at Andersonville well before my client ever arrived at the place. One of the men in charge of the camp at that time, told Mr. Spencer that he intended to “build a pen…that will kill more damned Yankees that can be destroyed in the front.” I remind the court that by the time my client arrived at Andersonville, the prison was already at its capacity and conditions were greatly deteriorated. The second letter was written by my client. In it, he implores his superior officer to do something about the poor quality of the bread given to the prisoners. Nothing was ever done about his request.

Judge: Very well. We have entered these two documents into the record. Please call your witness.

Defense: Your honor, I’d first like to call Colonel D.T. Chandler. As you know, Colonel Chandler inspected the prison at Andersonville and reported his findings to the Confederate government… Dr. Chandler, can you give us a brief overview of your findings at Andersonville?

Colonel D.T. Chandler: My report describes the problems with the water supply, particularly the dumping of refuse into the stream by the cookhouse and its use as a toilet, the problems arising from a lack of shelter, the lack of any systematic arrangement of the prisoners’ tents, the insufficient and poor quality of the food, and the problems arising from issuing rations uncooked without providing wood or utensils for cooking. I was especially disgusted by the conditions of the hospital and the general lack of sanitation throughout the prison.

Defense: You included suggestions with your report, didn’t you?

Chandler: Yes. I made numerous recommendations for improving the conditions at Andersonville. I suggested providing fresh vegetables, clothing, soap, medicines and bedding – and of course reducing the overcrowding by sending some of the prisoners away and not allowing any more to enter. I urged General Winder to do something about the terrible conditions.

Defense: The General Winder who was in charge of all prisoner of war camps in the Confederacy?

Chandler: Yes.

Defense: And what did he say?

Chandler: When I spoke of the great mortality existing among the prisoners, he replied to me that he thought it was better to let half of them die than to take care of the men.

Defense: Thank you, Colonel. Next, I’d like to call Lieutenant Colonel F.G. Ruffin…Lieutenant Colonel, you served in the subsistence department of the Confederate Army, didn’t you?

Lieutenant Colonel F.G. Ruffin: Yes, sir.

Defense: Was it easy supplying the army with food?

Ruffin: No, sir, of course not. From the beginning, there was more of less scarcity. We reduced rations at just about every level. The generals all complained, because they said they couldn’t keep their armies together on what we were giving them. But we couldn’t help it.

Defense: Thank you, Lieutenant Colonel. That will be all. Your honor, I’d like to now call Augustus Moesner, who can testify on whether Captain Wirz ever violated the rules of war. Mr. Moesner, in your experience as a guard at Andersonville, how did Captain Wirz feel about having young boys being held prisoner?

Augustus Moesner: I remember that there were about 40 or 50 boys inside the stockade, who had been taken prisoners, and Captain Wirz requested Dr. White to take some of them to the hospital as helps to the nurses or cooks there, because it was no use to keep those boys as prisoners of war. They would only get sick and die inside the stockade.

Defense: And what was the rule in regard to prisoners who got sick?

Moesner: Well, sir, when a man who had been ordered to wear a ball and chain complained that he was sick, a doctor was sent for, and if he found that it was so, the ball and chain would be taken off and the man would be sent to the hospital if necessary. Also, when new squads of prisoners came in, and there were men among them who claimed to be sick, a doctor was sent for. If the men were really sick, they were sent to the hospital. I also recollect also that once there was a man amongst them who told me he was a hospital steward in the army. I spoke to Captain Wirz about it, and the man was immediately sent to the hospital as a steward. He was paroled and was not sent into the stockade at all.

Defense: Did you at your headquarters or did Captain Wirz have anything to do with vaccination?

Moesner: I remember Dr. White gave an order, as the small-pox was increasing among the prisoners, that all men who came as new prisoners to Andersonville, who had not been vaccinated, should be vaccinated. But the order had been given by Dr. White and not by Captain Wirz. I remember Wirz once saying he would not care a damn whether they died of small-pox or not.

Defense: Do you know anything about Frado or “Frenchy,” who was brought in by the dogs?

Moesner: Frado was a Frenchman. He escaped seven times. I saw him brought back with a ball and chain on him once. A short time afterwards he escaped again. I don’t know how. The last time, he was brought back and sent to the stockade. Captain Wirz said he saw it was of no use of putting him in irons again. Rumor has it, they let the dogs at him. I saw only that his pants were torn up. I did not see that the dogs had hurt him. In fact, I never saw, knew, or heard of anybody dying at Captain Wirz’s headquarters who had been bitten by dogs. I never saw, knew, or head about Captain Wirz shooting, beating, or killing men in any way while I was there. I never saw, knew, or heard in any way of Captain Wirz carrying a whip while I was there. He never did.

Defense: But surely he had the power to punish the prisoners?

Moesner: Captain Wirz had the power to inflict other punishment besides putting men in the stocks. He had the power to put the ball and chain on them. I never saw a man bucked and gagged while I was at Andersonville. I don't know whether he could issue the order on that subject. I don't know how far his power went. I know of Captain Wirz ordering men to be whipped. I have heard him give the order to whip a man. That is another thing he had power to do. Captain Wirz had the power and exercised the power to direct that prisoners be caught by the hounds. He had that power. He put them in the stocks. I don't recollect any other punishments than what I have mentioned. Although Captain Wirz had the power to inflict all these other punishments, he had no power to put men in the chaingang, so far as I know, and I know about that just as I know about everything else. I never heard of Captain Wirz shooting, kicking, or beating a Federal prisoner while I was at Andersonville. I swear positively to that; I saw him pushing prisoners into the ranks, but not that they could be hurt. He was violent in these moments, cursing and swearing, as he always was with us, but he seemed harder than he was.

Defense: You swear positively that you never heard of a man being torn by the hounds?

Moesner: I saw that Frenchy had his pants torn. That is the only instance of hounds tearing the soldiers' clothes or flesh that I ever heard of.

Defense: Thank you. We now call Father Peter Whelan…Father, can you tell us of your experiences at Andersonville?

Father Peter Whelan: As a Roman Catholic priest, I spent more than three months at Andersonville ministering to those of the faith and to others in need of spiritual comfort. I was often inside the stockade from 9 a.m. to 4 or 5 p.m. from mid-June to about the beginning of October 1864.

Defense: From your intimacy with Captain Wirz while you were there, can you tell us what his general conduct, as to kindness or harshness, toward the prisoners was like?

Father Whelan: He was always calm and kind to me.

Defense: Was he to others, so far as you saw?

Father Whelan: Yes, sir. I have seen him commit no violence. He may sometimes have spoken harshly to some of the prisoners…There have been some violence charged upon him here which I never heard of being committed by him. I never heard of his killing a man, or striking a man with a pistol, or kicking a man to death. During my time in the stockade, I never heard of it. I never heard, either inside or outside, during my stay there, that he had taken the life of a man by violence.

Defense: If any such thing occurred, must you not have heard of it?

Father Whelan: It is highly probable I should have heard of it.

Defense: Your honor, the defense rests.

Judge: Very well. Will the prosecution make its closing argument?

Prosecution: Your honor, more than 100 witnesses have come forward to help the prosecution make its case. The evidence points to the truth. Mortal man has never been called to answer before a legal tribunal to a catalogue of crime like this. One shudders at the fact, and almost doubts the age we live in. I would not harrow up your minds by dwelling further upon this woeful record. The obligation you have taken constitutes you the sole judges of both law and fact. I pray you administer the one, and decide the other. To the defense’s complaints about the alleged vagueness of some of the testimony, we say, naturally the prisoners’ memories are a bit jumbled. They had in many cases lost track of what day, or even what month it was. They also witnessed so many horrible incidents on a daily basis that it should not be surprising if they were unable to fix with certainty an exact date of one in particular. And to the assertion that the defendant was only following orders we say that a superior officer cannot order a subordinate to do an illegal act, and if a subordinate obey such an order and disastrous consequences result, both the superior and the subordinate must answer for it!

Judge: Would the defendant like to make a final statement?

Henry Wirz: Yes, your honor. I am no lawyer, gentlemen, and this statement is prepared without the aid of my counsel…A poor subaltern officer should not be called upon to bear upon his overburdened shoulders the faults and misdeeds of others…It cannot be expected, neither law nor justice requires, that I should be able to defend myself against the vague allegations, the murky, foggy, indefinite, and contradictory testimony…The alleged murder of a prisoner named Chickamauga was described by at least 20 witnesses – and in as many different versions…William Stewart, another soldier I allegedly murdered, is as much a creation of the fertile imagination of the witness who testified to his murder by me as the conspiracy charged against me is a creation of the fancy of the prosecution…This court…is composed of brave, honorable, and enlightened officers, who have the ability, I am sure, to distinguish the real from the fictitious in this case, the honesty to rise above popular clamor and public misrepresentations…I cannot believe that they will consent to…consign to a felon’s doom a poor subaltern officer, who, in a different post, sought to do his duty and did it…May god so direct and enlighten you in your deliberations that your reputation for impartiality and justice may be upheld, my character vindicated, and the few days of my natural life spared to my helpless family.

Saturday, April 4, 2009

Sherman's March to the Sea: A Geography Lesson

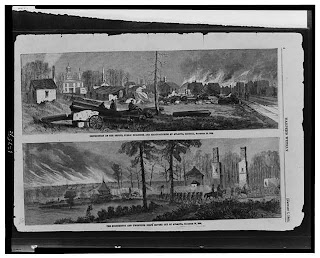

Image 1 (bottom): Ruins of depot in Atlanta, Nov. 1864, following the bombing by Union General Sherman’s army before its evacuation from Atlanta.

Image 2: A war-damaged building in Atlanta, Nov. 1864.

Image 3: A Harper’s Weekly illustration showing the destruction of the depots, public buildings, and manufactories in Atlanta, Nov. 1864. The 14th and 20th Corps are shown moving out of the city.

Image 4: The shell-damaged Ponder House in Atlanta, Sept.-Nov., 1864.

Image 5 (top): Sherman’s men tearing up railroad tracks in Atlanta, 1864.

Note: The above images are from the Library of Congress. Other images and documents can be found at http://georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu/1864.htm

I. Essential Questions

1. Was Sherman’s March to the Sea justified?

2. What were the geographic, economic, and demographic similarities/differences between the North and South during the Civil War?

3. When is “total war” or “hard war” acceptable?

II. New Jersey Core Curriculum Standards

6.1;A2-3;6.1;A5.

2. Formulate questions and hypotheses from multiple perspectives, using multiple sources.

3. Gather, analyze, and reconcile information from primary and secondary sources to support or reject hypotheses.

5. Evaluate current issues, events, or themes and trace their evolution through historical periods.

6.4;G1.

1. Analyze key issues, events, and personalities of the Civil War period, including New Jersey’s role in the Abolitionist Movement and the national elections, the development of the Jersey Shore, and the roles of women and children in New Jersey factories.

6.6;A5.

5. Apply spatial thinking to understand the interrelationship of history, geography economics, and the environment, including domestic and international migrations, changing environmental preferences and settlement patterns, and frictions between population groups.

III. Introduction

General William Tecumseh Sherman remains famous – or infamous – for his “March to the Sea.” He has been regarded by many Southerners as a horrendous villain of the Civil War. In 1864-65, U.S. soldiers under Sherman’s command marched through Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. They destroyed or confiscated agricultural produce, crops, and livestock. They destroyed huge numbers of railroad ties, destroyed factories, and burned warehouses. They also burned some houses belonging to Southerners – although not as many as the Southern public thought – and also burned some public buildings, including the South Carolina state capitol building. Destroying supplies and sabotaging the South’s transportation and manufacturing facilities deprived Southern armies of food and ammunition that that needed to keep fighting. Sherman’s tactics and willingness to inflict hardship on the South’s civilian population also may have helped end the war. (Source: http://www.americanthinker.com/2007/06/the_hard_hand_of_war.html).

In this lesson, students will examine the reasons or motivations behind Sherman’s March to the Sea and the North’s greater willingness to take the war to the heart of the Confederacy in 1864. They will also evaluate the consequences of these actions. While doing this, they will also come to understand the progress of the war prior to 1864 and the economic and geographic differences between the Union and the Confederacy. Students will conclude the lesson by bringing the discussion to the present time and debating if (or when) “total war” is acceptable.

IV. Strategy

The lesson will begin with students reviewing the photos from the Library of Congress shown above. Students will also watch an approximately 15-minute clip of Ken Burns’ Civil War documentary to become more familiar with Sherman’s March to the Sea. (Episode 8 of the VHS version includes Sherman’s plan to make Georgia “howl.”) The History Channel web site on the march may also be used as part of the introduction. Maps should also be provided (either from online or from the book Great Maps of the Civil War, which includes removable reprints of Civil War era maps).