Image 1 (bottom): Ruins of depot in Atlanta, Nov. 1864, following the bombing by Union General Sherman’s army before its evacuation from Atlanta.

Image 2: A war-damaged building in Atlanta, Nov. 1864.

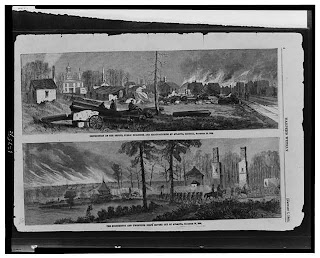

Image 3: A Harper’s Weekly illustration showing the destruction of the depots, public buildings, and manufactories in Atlanta, Nov. 1864. The 14th and 20th Corps are shown moving out of the city.

Image 4: The shell-damaged Ponder House in Atlanta, Sept.-Nov., 1864.

Image 5 (top): Sherman’s men tearing up railroad tracks in Atlanta, 1864.

Note: The above images are from the Library of Congress. Other images and documents can be found at http://georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu/1864.htm

I. Essential Questions

1. Was Sherman’s March to the Sea justified?

2. What were the geographic, economic, and demographic similarities/differences between the North and South during the Civil War?

3. When is “total war” or “hard war” acceptable?

II. New Jersey Core Curriculum Standards

6.1;A2-3;6.1;A5.

2. Formulate questions and hypotheses from multiple perspectives, using multiple sources.

3. Gather, analyze, and reconcile information from primary and secondary sources to support or reject hypotheses.

5. Evaluate current issues, events, or themes and trace their evolution through historical periods.

6.4;G1.

1. Analyze key issues, events, and personalities of the Civil War period, including New Jersey’s role in the Abolitionist Movement and the national elections, the development of the Jersey Shore, and the roles of women and children in New Jersey factories.

6.6;A5.

5. Apply spatial thinking to understand the interrelationship of history, geography economics, and the environment, including domestic and international migrations, changing environmental preferences and settlement patterns, and frictions between population groups.

III. Introduction

General William Tecumseh Sherman remains famous – or infamous – for his “March to the Sea.” He has been regarded by many Southerners as a horrendous villain of the Civil War. In 1864-65, U.S. soldiers under Sherman’s command marched through Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. They destroyed or confiscated agricultural produce, crops, and livestock. They destroyed huge numbers of railroad ties, destroyed factories, and burned warehouses. They also burned some houses belonging to Southerners – although not as many as the Southern public thought – and also burned some public buildings, including the South Carolina state capitol building. Destroying supplies and sabotaging the South’s transportation and manufacturing facilities deprived Southern armies of food and ammunition that that needed to keep fighting. Sherman’s tactics and willingness to inflict hardship on the South’s civilian population also may have helped end the war. (Source: http://www.americanthinker.com/2007/06/the_hard_hand_of_war.html).

In this lesson, students will examine the reasons or motivations behind Sherman’s March to the Sea and the North’s greater willingness to take the war to the heart of the Confederacy in 1864. They will also evaluate the consequences of these actions. While doing this, they will also come to understand the progress of the war prior to 1864 and the economic and geographic differences between the Union and the Confederacy. Students will conclude the lesson by bringing the discussion to the present time and debating if (or when) “total war” is acceptable.

IV. Strategy

The lesson will begin with students reviewing the photos from the Library of Congress shown above. Students will also watch an approximately 15-minute clip of Ken Burns’ Civil War documentary to become more familiar with Sherman’s March to the Sea. (Episode 8 of the VHS version includes Sherman’s plan to make Georgia “howl.”) The History Channel web site on the march may also be used as part of the introduction. Maps should also be provided (either from online or from the book Great Maps of the Civil War, which includes removable reprints of Civil War era maps).

The class will be divided into six groups. The three “Union” groups will examine primary source documents relating to Sherman’s March. These documents can include Sherman’s letter to Henry Halleck, in which we find Sherman’s famous “hard hand of war” explanation, a letter from Sherman to Grant, and Grant’s personal memoirs (pages 482-500).

The three “Confederacy” groups will examine the effects of the march through Southern eyes. Documents that can be used include The War-Time Journal of a Georgia Girl, 1864-1865 (Sherman’s March begins on Page 19), A Woman’s Wartime Journal: an Account of the Passage over Georgia’s Plantation of Sherman’s Army on the March to the Sea, as recorded in the Diary of Dolly Sumner Hunt, and a December 1864 Account of Destruction of Atlanta.

Each group should focus on the following questions and issues.

1. What were Sherman’s goals and reasons for the march?

2. Did Sherman’s march help solidify a Union victory? Why or why not?

3. Was Sherman’s march justified?

After allowing the groups to work on their own for about 20 minutes, the class should reconvene as a whole and explore the answers to the above questions. Questions 1 & 2 should lead to a discussion on the economic, social, and cultural differences between the North and South and Sherman’s desire to strike at the South’s resources and ability/desire to continue to make war. Much of the debate should focus on Question 3, since it allows the students to examine history from multiple perspectives.

Note: The lesson can also be extended to include Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign (Episode 7 of The Civil War), if desired. In this format, the class can be divided into four groups. Two would examine Sheridan’s campaign (one from a Northern perspective, one from a Southern perspective), while two would examine Sherman’s march (one from a Northern perspective, one from a Southern perspective).

Additional resources:

http://www.history.com/classroom/admin/study_guide/archives/thc_guide.0545.html

http://www.pbs.org/civilwar/classroom/lesson_sherman.html

V. Closure

There are a number of activities that can be used as closure for this lesson, or to extend the lesson over additional class periods. Students can compare Sherman’s march with other instances of total war in World War I or World War II, or can look at the on-going debate over the justification of total war by researching the topic in contemporary articles about the war in Afghanistan or war against terrorism. Questions may center on the acceptability of civilian casualties and the justification for targeting non-military targets during a war. In this way, students can debate the issues of total war and its effects from a modern perspective. Students can also debate Sherman’s legacy. For example, they (as suggested on the PBS website) can conduct a mock trial of Union officers who engaged in “total war” practices.